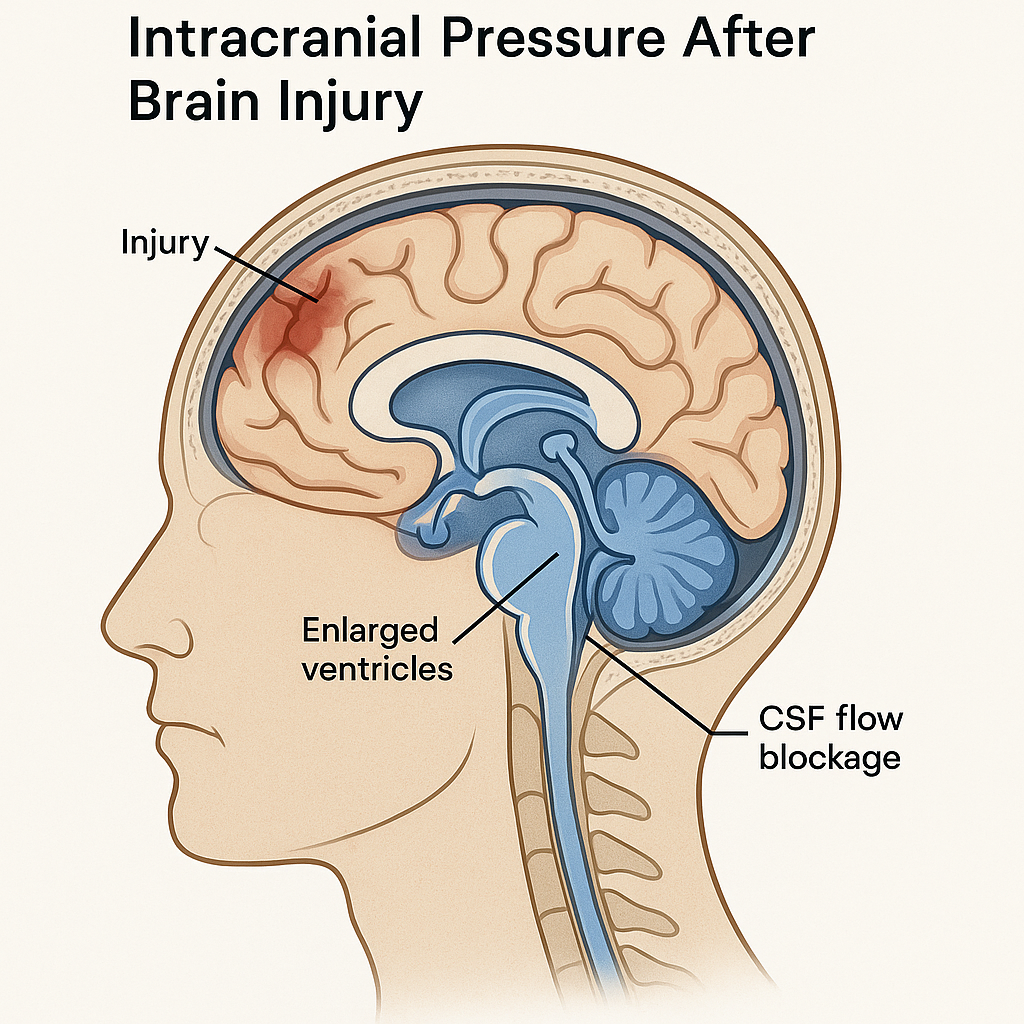

After a brain injury, one of the most serious and potentially life-threatening complications is a rise in pressure inside the skull. This can occur because of hydrocephalus, where excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) accumulates, or because of swelling, bleeding, or other disruptions in the brain’s normal balance. When pressure builds, the brain has no room to expand, and critical tissue can become compressed—interfering with blood flow and oxygen delivery.

What Is Hydrocephalus?

Hydrocephalus literally means “water on the brain.” In medical terms, it’s a condition where cerebrospinal fluid collects within the brain’s ventricles (fluid-filled spaces). Normally, CSF cushions the brain and spinal cord, circulates nutrients, and removes waste. But after a traumatic brain injury (TBI) or other forms of acquired brain injury, this circulation can become blocked or impaired.

Causes of Hydrocephalus After Brain Injury

- Bleeding (intraventricular hemorrhage): Blood can block the CSF pathways or change how it’s absorbed.

- Swelling or scarring: Inflammation can narrow or obstruct CSF channels.

- Damage to absorption sites: The arachnoid villi (tiny structures that absorb CSF) can be damaged by trauma or infection.

When fluid builds up faster than it can drain, the ventricles enlarge and pressure rises.

Understanding Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)

Intracranial pressure refers to the pressure exerted by brain tissue, blood, and CSF within the skull. The skull is rigid and closed, so any increase in one component must be balanced by a decrease in another. If that balance fails, ICP rises.

Common Causes of Elevated ICP After Brain Injury

- Cerebral edema (swelling)

- Intracranial bleeding (hematomas)

- Obstructed CSF flow (hydrocephalus)

- Venous congestion or infection

Even a modest rise in ICP can reduce cerebral blood flow and oxygenation, leading to secondary brain injury.

Signs and Symptoms to Watch For

The symptoms of hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure often overlap. In both, the key danger is compression of brain structures and decreased perfusion.

Early signs may include:

- Persistent or worsening headache

- Nausea and vomiting

- Vision changes or double vision

- Drowsiness or confusion

- Problems with balance or walking

Severe or late signs can include:

- Pupils that are unequal or slow to react

- Seizures

- Sudden loss of consciousness

- Irregular breathing or heart rate (a medical emergency)

In infants or very young children with brain injuries, hydrocephalus may also cause an enlarged head or bulging fontanelle.

Diagnosis and Monitoring

Clinicians diagnose hydrocephalus and raised ICP using a combination of imaging and physiological monitoring.

- CT or MRI scans show enlarged ventricles, swelling, or masses.

- ICP monitoring devices (like an intraventricular catheter or fiberoptic sensor) measure pressure directly inside the skull.

- Neurological exams track changes in consciousness, reflexes, and pupil responses.

Continuous monitoring is vital in intensive care units, where early intervention can prevent irreversible damage.

Treatment Options

1. Surgical Drainage or Shunt Placement

When hydrocephalus is confirmed, surgeons may insert a ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt—a flexible tube that drains excess CSF from the ventricles into the abdomen.

Alternatively, a ventriculostomy (temporary external drain) may be used for acute relief and pressure control.

2. Medical Management

For general intracranial pressure management:

- Osmotic agents like mannitol or hypertonic saline draw fluid out of brain tissue.

- Sedation and pain control reduce metabolic demand and agitation.

- Careful fluid balance prevents excess accumulation.

- Controlled ventilation lowers carbon dioxide levels, temporarily reducing cerebral blood volume.

3. Addressing the Underlying Cause

If swelling, bleeding, or infection is responsible, doctors target that condition directly—by removing hematomas, treating infections, or managing inflammation.

Long-Term Outcomes and Rehabilitation

Some patients recover fully after appropriate treatment, while others may experience lasting effects such as:

- Gait and balance issues

- Cognitive or memory challenges

- Vision or speech difficulties

- Need for ongoing shunt management

Regular follow-up is crucial because shunt systems can fail or become infected, sometimes years later. For survivors of severe brain injury, managing hydrocephalus and pressure is often the first step toward stabilization and rehabilitation.

Preventing Secondary Injury

Preventing and controlling intracranial pressure is a cornerstone of acute brain injury care. Every minute counts. Early detection, precise monitoring, and coordinated neurocritical care greatly improve outcomes and reduce disability.

Families can help by recognizing warning signs—especially changes in alertness, headaches, or vomiting—and ensuring rapid medical attention.

Key Takeaway

Hydrocephalus and increased intracranial pressure are among the most critical complications after brain injury. With timely intervention, close monitoring, and comprehensive care, many patients can recover function and move forward in rehabilitation.